[an error occurred while processing this directive]

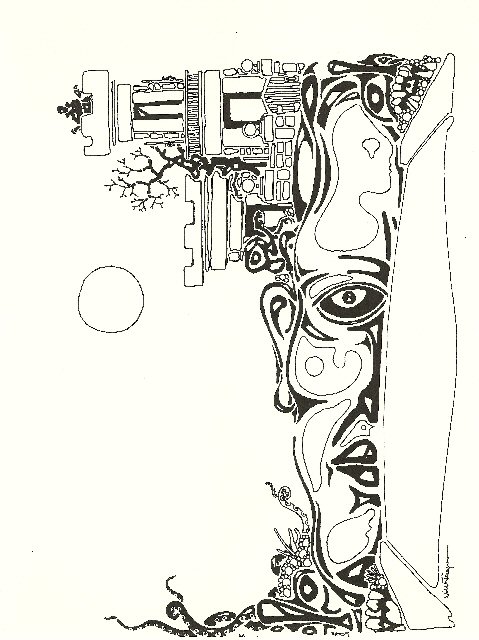

Artwork: Queen Maub 2 by Will Jacques

Binding

Gina Wisker

I like to get things right, precise, rendered, ordered, neat and in the right place like a well bound book, knowing where you can find it, in order on the shelf where you put it, catalogued, exactly in the right place. People think if you are a librarian your job is stamping books out for some dear old lady or a bunch of children in a public library or going round looking stern at the talkers and whispering ‘ssh!!’ People are, in my experience, very ignorant about the exactness, the complexity and the delicacy, the detail, the precision of the work involved in being a rare books librarian, in an internationally renowned library, a rare books librarian, who tends the books, like rare discoveries, like delicate plants, dusts them, ensures their labels and their bindings are perfect.

And, indeed, it is somewhat of an irritation when someone comes along and moves the book you have so lovingly placed in just the right position, moves it, fiddles with it, even momentarily borrows it – only inside the library of course – for these rare books cannot actually leave the library itself – no, they need the right temperature and humidity, and the right tender care to last – to survive – and this person takes the book into their life, out of your life, into their world and on, so to speak, their shelf. But tracking this invasive movement then is essential, tracing through time and place, date and location, and ensuring that whoever has let whoever borrow this book, only for use in the reading carrels in the library itself, that this person returns it to its rightful place or better still left on the stacking trolleys so that I might return it exactly where it came from, preserve it there, clean and tend it.

Preservation is a very important part of my profession, preservation and provenance, the seeking of origins and the fixing of these in fact are my expertise. Preservation is more manageable in the rare books division, more manageable than in the main library, which has a kind of free-for-all atmosphere. In the main library, indeed, some of the more nefarious of the undergraduates in the past would, just before exam time and just before open book examination in particular, sneak individual copies of the very book they needed and hide such copies out of order, in secret places, lost among the alphabetically other, or the discipline different, deceive those searching for the clues to the whereabouts of the rarity, hide them, secrete them in plain view indeed.

While I deplore this behaviour, it has sometimes been necessary to behave in that way myself. If there is a particularly beautiful, precious book, dear to me as no human being could ever be so dear, a book I love and have catalogued, tended and cared for, I might also place it in plain view but in the wrong place – under my own private cataloguing system. This is indeed like coding, cataloguing with my own secret system. For cataloguing resembles detective work of course, the tracking down of provenance, the precise identification.

To find this hidden text you would need to work out the geology of the mind, the geography of my imagination and the history of my previous movements. For example, Ars Grammatica would of course notionally be in Literature in the rare books section, possibly related to its concerns or to its date of origin, and then alphabetised for easy discovery, reference and temporary acquisition. For, of course, though for some books lending is an option, we must be reminded that for others it is just use in the library carrels that is allowed and they, the books, remain essentially in their home. Some others, rare beyond your wildest imagination, those first folios of Shakespeare, that edition inscribed in the flyleaf with the names of Elizabeth the 1st and her lover entwined – these books cannot even be summoned up by the itinerant rare books scholar from elsewhere bent on somehow cataloguing and defining them himself within the bounds of his own system – or even hers – for indeed there are increasing numbers of women entering our skilled profession, however charming and disorganised one finds so many of them. There are of course a very few in my experience with quite the rigour and the eye for minutiae, the sense of exact order and precision, the seriousness of our work.

To return to the rare book in question, this imaginary rare book, this loving being as I would like to imagine it, if one wants, let us say, to keep this book permanently in ‘a safe home’ under one’s own system, to which only you in a sense have the key, the cataloguing key, you can of course lovingly place it in a different disciplinary section where, if alphabetised for instance, it can go unnoticed, seeming to fit into someone else’s scheme, but in fact, into yours, or rather, in this instance, mine alone.

It is not the contents of the books themselves which always interest me, oh no, some of these contents are at best repetitive. Who wants yet another old family Bible? But their delicate bindings, their skins, so to speak, tell you so much more about their provenance, their rarity, their worth. The main fascination I have is with these very skins, with old book bindings, so delicate, so beautiful so hard wearing and essentially both elastic over many years and almost alive, those books bound historically in skin. Some say in human skin. Mostly of course, it is just at best pig skin, or calf perhaps. But, indeed, it is recorded that there have been some people who have dedicated their final most intimate personal garment to clothe rare books, so to speak. In this respect, they can be said to have saved their own skins, to last and outlast the pettinesses of the everyday, to remain, wonderfully, perfectly preserved. We have just a few of these. Of course, the practice, mostly found amongst the Spanish, was outlawed hundreds or so years ago but some of the rare books do exist. One could perhaps find them in, for instance, the holy Brothers’ libraries in Ireland, in the great library of Trinity, Dublin, perhaps, in the Pugin library in Maynooth, served by dedicated librarians as if theirs was a religious calling, which of course it is. Up those twisting stairs past the stores of ancient clerics hiding the secrets of power. They are also in the Thomas Fisher rare books library in the University of Toronto, or the Turnbull in Wellington, or even the British Library. Indeed, it is said, and has been authenticated, that many of these very rare and sacred books are themselves bound in human skin.

Ah yes, and it was in the old British Museum Library itself, when we were just young students, that I and a certain young lady trainee librarian studied opposite each other sharing new discoveries about cataloguing strategies, the finer points of binding, the finger prints indeed or armorials embossed upon the rare, skin covers of those rare books – but I digress.

Sometimes it is lonely being a librarian, but my books are my company, they talk to me in a way, and I love and care for them. The past is a living place for me with my books, with the treasure they offer me, not so the past of those problematic human relationships, much less successful than any long lingering time with one of my favourite beloved books. And sometimes even the memories are best locked away behind a mental door of which only I know the location, in a room in the mind perhaps, a safe place where they can lie and leave life alone.

I don’t know really why I thought to look up the Friends Reunited site that late night in the reserve combination section of the rare book archives. But one of my other favourite indulgences is seeking for archival information and the location of rare books for us to acquire, using the Internet, which, it has to be said, is a varied and often almost unimaginably, endlessly, rich treasure trove of information, some of which, like this finding that significant evening, some of which can lead to some of the most important tracings and trackings and finally the most important acquisitions.

Seeing her name there brought such a lot back, retrieved it from

where time and memory had stored it, shelved it, filed it. Her name.

Newly discovered, it returned a kind of richness, like finding a rare

tract maybe hidden from view for years – or newly acquired.

Her name was hidden, of course, behind or beneath her married

name, occluded by that past in between, but some subtle silent detective

work revealed the full details.

Those were such different times. I was reminded of those youthful

undergraduate days and times long ago when neither of us of course

had the slightest idea of how we would turn out.

And there was so little information on the website! Settled there, widowed, lives alone, many things in common now perhaps, as life has moved on for the both of us. It was worth the tentative message, after all, she did say she was eager to get in touch with old friends. Perhaps having recently moved to a new town herself she was isolated without many people who knew her. Perhaps, with so many changes, she knew it would be good to get back into an old life or at least shake herself down, dust herself off and replace herself in some old or new relationships, systems, life.

To receive a message a few days later was an absolute delight! Just like the richness of finding exactly that reference, exactly that edition, exactly that text, or that binding.

Starting from that moment on, our growing correspondence was something to liven up the duller ends of the darkening autumn days as they drifted inevitably into the gloom and dark of winter. Every delicate detail revealed, every exchange brought us somehow closer. I was certainly ready to cast to the furthest recesses of my memory whatever it was that had ultimately come between us, all those years ago. She said at the time something about my smothering her in our relationship, something about how dead it had all grown, how she felt too young to be so tied down in relationships generally. She felt, she said, somehow labelled, incarcerated, embalmed. Forgivable perhaps in one so young! For we were just barely into our twenties! my goodness. Not a thing to dwell on now. She sounded, also, a lot calmer, more focused, more mature in her correspondence.

Though, of course, some less than pleasant memories, unfortunately, silently invaded my peace, and my planning for our intended reunion despite my best intentions. Not such a good experience to recall the searing pain, that sense of being slowly stretched as if on a rack, the tortured, invasive, physically unbearable pain of being rejected for what – I cannot recall – I really cannot. The pain of our break up was at an intensity my body has long since denied or forgotten. Not something to bring up now, no indeed, in this delightful discovery of our new friendship.

It was a particularly fine idea now to meet and choosing a suitable date became a topic on which to agree – so difficult to align exactly our very different worlds. But we did it! We fixed a time mid-winter, a December date, to liven up the darkening days, the days and nights when everyone keeps themselves to themselves and hardly even notices anyone they know on the street, should they pass them. A time for hot cocoa in front of the fire at home, for poring over old collections and new acquisitions, for reminiscing, for taking stock.

And as the time got closer, of course, to some extent we both had our misgivings! Conducting the beginnings of a new love affair, perhaps, or rekindling an old one or just maintaining an acquaintance so much more straightforward at the controlled distance afforded by email exchange.

I was mindfully concerned, for example, that she might find me a

little set in my ways. She, it seemed, was equally concerned that

I would notice what she referred to as the ‘ravages of time’

on her skin, her outward self. As the time got closer, she also confided

a worry that one so naturally ordered and serious as I would find

her filled with trivia, disordered. I assured her that I looked forward

to the delightful energy that this variety, her adventures, her range

of hobbies and activities represented in my otherwise very ordered,

even mundane existence.

I believe it is important to plan for every exigency and I took special

care with this evening, determined to enjoy its richness, to take

from it something to add to my personal store of memories, something

to preserve and thus to understand and revisit.

It really was an excellent idea to meet. My flat, its neat shelves of my own rare books, lovingly catalogued. Opera, some particularly fine wine and the cooking of that meticulously researched and chosen meal. The delicate portions of veal, skinless, the petit pois, the jus carefully heated and held at exactly the right temperature. It seemed – at least for a while – the perfect evening.

She looked around my tidy apartment and clearly admired the neat, full bookshelves. ‘You used to be some kind of expert on binding didn’t you?’ she enquired. Yes, indeed, she certainly touched an important part of my life there and one in which I have become an expert, an international expert, and as it happens, very pertinent to our evening together. I pointed out the work I brought home to prepare. A carefully organised pile of precious, some newly discovered, books, whose covers have been ruined by neglect, by mildew, by age, by water by – use. I explained a little then about the precision of this work. ‘Yes, indeed. I have been researching the specific details of a particular form of binding favoured by the Spanish several hundred years ago. It is usually carried out using pig skin, although there is also evidence of the use of human skin – more supple – donated post mortem, of course’. She seemed to be interested, so I continued. ‘Research shows the importance of the insertion of needles and the gradual fine stretching accompanied by precisely located tenderising, often conducted through a form of beating. During this time, however old, the donated skin might actually be, it must remain supple or it would lose its fine ability to contour round the book, indeed, just like its own skin.’ The meal was ready, so we sat down, to eat and appreciate the subtleties of this gourmet meal and our reunion.

Candle light is both flattering, casting shadows which hide some of those little secrets we would rather retain as our own, and cruel, when directly lighting a face which once was so much younger. But although a little disillusioning, that was not really the problem. The problem really, the problem was not that she had changed so much, indeed she had changed little, her body plumped out more, the lines round her face now visible, in places overwhelming, in places reminding you of an aged parchment stretched and crumpled. No, it wasn’t so much that she had changed, as that she had not changed much at all. Over the carefully prepared veal there was an intrusive return to a gradually familiar level of paltry gossip. There was a nagging away at small issues to do with the quality of the wine perhaps, the reason for the vegetables being a little underdone, as they were, deliberately ‘al dente’, of course. She was somehow unable to recognise and reward the large amounts of time I had put into the food preparation, inspecting the perfect pungent herbs for this meal to liven it up, to embellish it – these she missed as indeed she had done with the food I had cooked her all those years ago, I recalled, when we were young students together, in another time, another place. The conversation grew rather dull, accounts of people I cannot remember, trifles repeated and replayed, hauled into the open to sit blinking in the light for re-scrutiny. Unnecessary, in my view, to bring everything out into the open in that way, to cast some kind of cruel light on the shortcomings of the past, let alone those of the present, so more noticeable in the brighter light of the kitchen where we carried the first course plates back out for me to wash later. I think it was over the dessert that I began to really tire of the conversation: trivial, jumbled, worded occasionally a little inappropriately, certainly out of place in the environment of my neat flat, uncluttered except for the lines of perfectly bound, lovingly arranged books on the floor to ceiling book shelves. I think I was tiring of this whole event when she got up from her seat at the end of the dessert, leaving some of it still unfinished and certainly not commented on, got up and walked over to the books. She started to take each one out of its particular place and to finger them, not lovingly and reverently as you might recognise was appropriate, but rather roughly, coarsely, talking over the pages as she flicked through them, missing the embossed armorial on the covers, the elegantly inscribed frontispieces, the film paper between the original prints of those pictures. ‘And you were saying about binding?’ she began. ‘This binding in skin??’ ‘Yes,’ I continued, ’ The experts are unanimous about preference for fresh, supple skin.’

‘And the preparation?’

‘Indeed, there are some rather obscure footnotes at this point seeming to hint at what might appropriately be termed flaying i.e. the skinning perhaps taking place before actual death.’

Footnotes. Details. Valuable information.

‘Fascinating’, she said.

I winced when I noticed how she stretched the binding of one of my favourite books and then, finished with it, still talking, jammed it back, in the wrong place. The wrong place for some things. Indeed, perhaps it is the wrong place, the wrong time, for some things, and the right time and place for others.

I remembered rather too clearly now some of the reasons for our breaking up. The intolerable sense of chaos she brought, so odd for a fellow librarian, even one of a very different cast. And I recalled the unpredictable, the cut out of the blue, out of nowhere, that cold way she had suddenly left me. It was a renewed, a finely tuned pain but then it had been an utterly excruciating severance, modulating over the months between sudden sharp, incisive pain and then lingering aeons of loss.

It was certainly time for the dessert wine. Somewhat extra sweet she thought it, perhaps.

But it is so important is it not, to preserve these fleeting moments? to catch them as they go, and as they are on the point of decay, as was this. To capture them again as if in aspic, somehow, as if preserved in plastic or glass like those tiny scenes in the paperweights on my desk, something perfect, exquisite and unsullied.

She’s sleeping now, or so it seems. At last quietened, less frenzied than she was for those unpleasant few moments. And as her face relaxes, well prior to rigor, I can see the lines unfurl. The laughter lines, the lifelines, the wrinkles are coming free and something of that old loveliness, that clarity of skin and glow seems, in the delicate light of this room late at night, to be preserved. Of course it will be a long job, and at times painful in so many ways, but the very essence of what really matters about her and our time together now, and in the past, will indeed be preserved.

There is such a large pile of these precious, some newly discovered,

books, whose covers have been ruined by neglect, by mildew, by age,

by water, by – use. Each will be lovingly covered, each re-grafted

and each carefully placed in full view, preserved forever,

to be admired by the connoisseurs of bindings in specific, special

places in the library. I can’t wait.